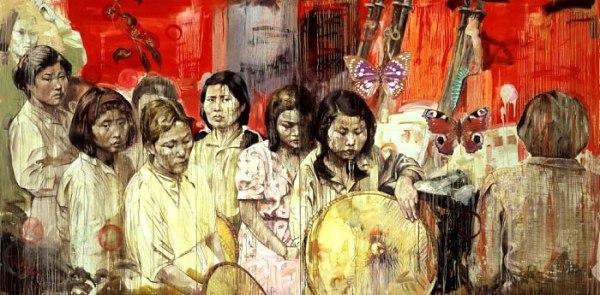

The (hopefully) Unforgotten: Valor and our comfort women

The (hopefully) Unforgotten: Valor and our comfort women

For too long the National Youth Commission (NYC)

has been used by various administrations as training ground for

next-gen storm troopers. So it was a pleasant surprise to find an NYC

Holy Week email asking Filipinos to “Remember Stories of Comfort Women” while celebrating Araw ng Kagitingan.

A statement from NYC Chairman Leon Flores III says:

“Sa darating na Araw ng Kagitingan, kinikilala rin ng NYC ang ating mga lolas at ang kanilang kagitingan at lakas noong Japanese occupation. Mahalaga na ating malaman ang kanilang mga kuwento, kung paano sila inabuso, sinaktan, ginahasa at pinilahan ng mga sundalong hapon sa mga ‘comfort stations’. Hanggang ngayon, wala pa silang nakakamit na hustisya at marami sa kanila ang namatay na. Alamin natin ang kanilang mga kwento bilang pagpapahalaga sa kasaysayan.”

(As we celebrate the Day of Valour, NYC also acknowledges the courage of our grandmothers during the Japanese occupation.

It is important that we appreciate their narratives of horror and

humiliation – how they were abused, raped and harmed in the comfort

stations. Until now, they have not attained justice and several of them

have already passed away. Let us value our history by knowing their

stories.)

(As we celebrate the Day of Valour, NYC also acknowledges the courage of our grandmothers during the Japanese occupation.

It is important that we appreciate their narratives of horror and

humiliation – how they were abused, raped and harmed in the comfort

stations. Until now, they have not attained justice and several of them

have already passed away. Let us value our history by knowing their

stories.)“The struggle of Filipino comfort women may have several layers of issues attached to it already. What is both important and urgent is that our lolas know that young people are aware of the issue and are one with them in their fight for justice. We hope the young will realize that it is both a women’s issue and importantly, an issue of the country’s sovereignty.”

I’ve never met Mr. Flores and don’t know his information people. But

they seem to be holding themselves apart from the general partisan

clangor of the body politic. Also, they seem to give peers the respect

due thinking individuals. It’s impressive how these young people show

enough discipline to not mount the soapbox in this passage:

“During the Japanese occupation in the Philippines, several women were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military in what was termed as ‘comfort stations’. A Motion for Reconsideration (MR) is now pending with the Supreme Court against the decision (Vinuya vs. Romulo) penned by Justice Mariano del Castillo.”

SALT ON THEIR WOUNDS

The del Castillo reference here involves the notorious plagiarized decision that led to the impeachment of the magistrate. The Vinuya decision threw out the petition of 70 Filipino comfort women

seeking Philippine government support in their fight to wrest a formal

apology and reparation from Japan for the horrors visited on them during

World War II.

The gist of the SC comfort women controversy is, that not only did del Castillo plagiarize the works of the works of Ivan Criddle, Evan Fox-Descent, Christian Tams, and Mark Ellis, he plagiarized writings supporting our

comfort women. As comfort women counsel Romel Bagares notes, he stole

and then used these stolen fruits in a twisted bid to legitimize his

ruling.

Del Castillo is on extended leave due to ill health so there’s not much likelihood of another Senate impeachment trial right after that of Chief Justice Renato Corona.

(For those who may want to know more, try to read the story of Lola

Rosa, Maria Rosa Henson. She was the first Filipina Comfort Woman of

WWII to come forward publicly on September 12, 1992. She died in 1997,

still fighting for justice. Here’s an excerpt from the book. Those who want to read the Philippine government study that aimed to provide aid to the surviving comfort women.

A special United Nations-commissioned report

has found that the government of Japan orchestrated the enslavement of

“comfort women” as part of their policy of war. Filipinos, to be sure,

were not the only victims. Koreans, Chinese, Malays, Indonesians,

Burmese — no one escaped the cruelty.

Enslavement here includes “gang rape, forced abortions, sexual violence, human trafficking,

and other crimes against humanity”.

and other crimes against humanity”.

A summary of the report states:

“Tens of thousands of Filipino women, some of them as young as thirteen years of age, were either abducted from their homes or streets and brought to ‘comfort stations’ where they were raped daily by Japanese soldiers.

In addition to the sexual violations, the comfort women suffered other bodily injuries due to constant beatings inflicted by the Japanese soldiers in the course of the rape. Chopping of women’s breasts and forced abortion were also prevalent.”

The report came out in 2003. This was three years after the Women’s

International War Crimes Tribunal 2000 included rape and sexual slavery

as “crimes against humanity”.

This was three years after the Tribunal affirmed what various WW2

resistance movements have long claimed: That Japanese troops could not

have enjoyed such regular, untrammeled access to sex slaves without

approval from their highest military and civilian — S T A T E —

officials.

A study by the Philippine government from 1997 to 2002 estimates there were over 1,000 enslaved women in this country. They were taken to some 17 comfort stations scattered all over Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. The Digital Museum on the Comfort Women Issue lists the locations of their enslavement, with an accompanying map.

“In Manila… there were 12 houses of relaxation (comfort stations) and 5 brothels for privates and non-commissioned officers. War prisoners testified that there were 5 or 6 comfort stations where Korean, Filipino and Chinese women worked. On the island of North Luzon comfort stations existed at Bayonbong(1). In the Central Visaya region on the island of Masbate(3) there was a comfort station named “Military Club”. At Iloilo(4) on the island of Panay two comfort stations existed. It can be ascertained that in 1942 in the first one 12 – 16 women worked and in the second one 10 – 11 women. At Cebu(5) on the island of Cebu a Japanese proprietor opened a comfort station. At Tacloban(6) on the island of Leyte in a comfort station managed by Filipinos 9 Filipino women worked.

In Burauen(7) of the same island a comfort station was opened by August 1944.

In Butuan(8) on the island of Mindanao a comfort station was opened with three Filipino women in 1942. And it is known that in Cagayan(9) of the same island the third comfort station was established in February 1943. That means that there were three comfort stations in Cagayan. In Dansaran(10) in the central part of the island there was a Comfort station. In Davao(11) of the island there was a comfort station where Koreans, Taiwanese and Filipinos were brought and forced into service.

Another analysis on the report shows just how organized and efficient the Japanese were in their enslavement of women:

Only Japanese soldiers were allowed to frequent the “comfort stations” and were normally charged a fixed price. The prices varied by the women’s nationality.The rank of the soldier determined the length of time allowed for a visit, the price paid, and the hours at which the soldier was entitled to visit the comfort station. At least a portion of the revenue was taken by the military. According to the testimony of a survivor quoted in the report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur, from 3 to 7 pm each day she had to serve sergeants, whereas the evenings were reserved for lieutenants.The Japanese Army also regulated conditions at the “comfort stations,” issuing rules on working hours, hygiene, contraception, and prohibitions on alcohol and weapons. “Comfort women” were recorded on Japanese military supply lists under the heading of “ammunition” as well as under “Amenities.” Army doctors carried out health checks on the “comfort women,” primarily to prevent the spread of venereal disease. The “comfort women” system required the deployment of the vast infrastructure and resources that were at the government’s disposal, including soldiers and support personnel, weapons, all forms of land and sea transportation, and engineering and construction crews and matériel.

There is no more cruel euphemism than the term comfort women.

Whatever the Japanese thought they provided the would-be conquerors of

Asia, these women endured hell during and after the war. In the

conservative societies pillaged by the Japanese military, most spent the

decades following World War 2 nursing sorrow and anger and shame.

Harper Lee said it best in her novel, To Kill A Mockingbird:

“Courage is not a man with a gun in his hand. It’s knowing you’re

licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no

matter what. You rarely win, but sometimes you do.”

The UN special rapporteur’s report stressed Japan’s intransigence and its effect:

Almost fifty-six (56) years have passed since the abominable wartime sexual slavery, but the Japanese government still fails and refuses to acknowledge its legal responsibility to the Filipino comfort women, so the painful experiences and the psychological trauma suffered by the Filipino comfort women have remained unabated up to now.

A decade ago, there was already a weary air to the struggle. But even as late as 2007, Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has said there is no evidence that women were forced to become sex slaves by the Japanese army during World War II. This is what he said:

“There has been debate over the question of whether there was coercion… But the fact is, there was no evidence to prove there was coercion as initially suggested…That largely changes what constitutes the definition of coercion, and we have to take it from there.”

The issue is an emotive one for the East Asian region

|

“The issue of military sexual slavery during World War II should be

seen from the perspective of the women-victims,” says Galang. “Justice

should be delivered soon – while the Lolas are still alive. Now is the

time to take more aggressive action to pressure the Japanese government

to make apology and reparations.”

“It is the task of the present generation to prevent historical repetitions of severe violations of human rights.”

Too little of our young people remember the plight of the comfort

women. There’s precious little to be learned about them in school books —

where most space is reserved for warriors.

That’s partly why the NYC move is so welcome. Our comfort women need a

new generation to carry on their fight. For valor is not just for

warriors. As we celebrate “Araw ng Kagitingan”, let us salute the brave

women still fighting for justice in the twilight of their lives. And let

us not abandon their quest, nor let governments forget.

***

Araw ng Kagitingan “2B Commemorative Bicycle Tour.”

For you active types, here’s a release from the Department of Tourism that may interest you.

The 2B Commemorative Bicycle Tour is part of the official “Araw ng Kagitingan” activities approved and endorsed by the National Steering Committee on National Observance led by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

2B stands for Balara and Bilibid. The tour monumentalizes the two sites where Filipino guerrillas mounted victorious military action against the Japanese occupation forces. In Balara, a guerrilla town unit was able to rescue the Balara filters from demolition just a few days before the start of the Battle for Manila. In Bilibid, on the other hand, guerrillas mounted a daring raid to rescue their comrades held in New Bilibid Prison. They were able to execute the military operation successfully with lightning speed, surgical precision and without casualties. Sixty-six years later, it still shines as a Filipino feat of arms.

The route that connects the two sites passes through the eastern side of Metro Manila. From Quezon City, it goes through Pasig and traverses the old Spanish road that connected the former parts of Rizal to its former capital. The 2B Tour is more than 35 kilometers one way. The tour will include a return trip with scheduled rest stops along the way.

The 2B Tour is open to all cycling enthusiasts. It’s not a race and will be run at a leisurely pace of 15 to 20 kilometers per hour. The challenge is to complete the bike run. The route offers an alternative for cyclists who want to head south or north without passing through EDSA, C-5 or the SLEX service roads.

0 Mga Komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento

Mag-subscribe sa I-post ang Mga Komento [Atom]

<< Home